Nevertheless, the latest phase of the crisis, which began at the latest with the pandemic and the surge in inflation, makes a fascist option at least viable, especially in countries with corresponding “traditions.” The fundamental upheaval in the process of crisis and its handling of contradictions was initiated by the pandemic-induced crisis surge. The war in Ukraine is in fact a reaction to this new crisis phase, which is putting an end to neoliberal globalization. This phase is characterized by stagflation, deglobalization, protectionism, active industrial policy, nearshoring and vertical integration.

The four decades of neoliberalism – from the 1980s to around 2020 – were in fact a reaction to the crisis, and they prolonged the unfolding of the internal contradiction of capital. This fundamental contradiction of the capitalist mode of production unfolds as follows: Productive wage labor forms the substance of capital, but at the same time the process of capital valorization strives to displace wage labor from the production process through competitive rationalization measures. Marx introduced the ingenious term “moving contradiction” for this auto-destructive process. This contradiction of capitalist commodity production, in which capital minimizes its own substance, wage labor, through competition-mediated thrusts of rationalization, can only be maintained by “moving,” by the continuous expansion and further development of new fields of exploitation in commodity production. The same scientific and technological progress that leads to the melting away of the mass of expended wage labor in established branches of industry also gives rise to new branches of industry or production methods.

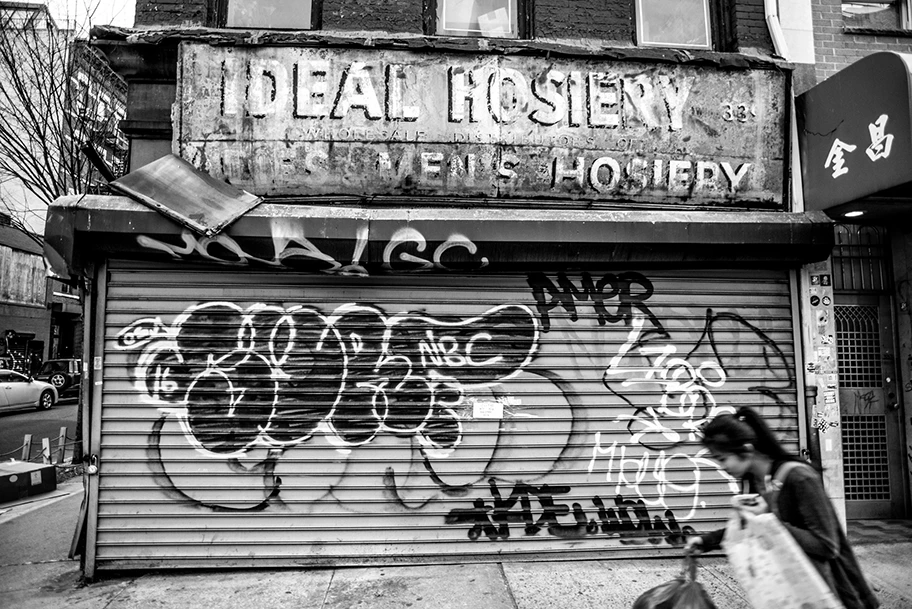

The result of this is precisely the kinds of change to the overall industrial structure – the ability of capital to constantly “reinvent itself” – that the bourgeois apologists of capitalism are so proud. Since the beginning of industrialization in the 18th century, the capitalist economy has been characterized by a structural change in which the textile industry, heavy industry, the chemical industry, the electrical industry and, most recently, Fordist vehicle manufacturing served as leading sectors that exploited wage labor on a massive scale. With the advent of automation and the IT revolution, the process of changing the structure of industry began to fail in the 1970s and 1980s. These new technologies created far fewer jobs than were rationalized away by their application to the economy as a whole. The productive forces thus burst “the fetters of the relations of production” (Marx) and capital came up against an “inner barrier” (Robert Kurz) to its ability to develop.

How Neoliberalism “Rescued” Capitalism

That capital as a moving contradiction had reached its inner limit was demonstrated very concretely in the crisis period of stagflation that followed the post-war boom, as no new leading industrial sector with mass valorization of wage labor could be developed. The late 1970s and early 1980s were characterized by anemic economic growth, frequent recessions, rapidly rising mass unemployment and an inflation rate that sometimes reached double digits. From a historical perspective, the stagflation of the 1970s – a portmanteau formed from the words stagnation and inflation – was precisely the period of crisis that paved the way for neoliberalism, as Keynesian crisis coping strategies has failed.In addition to destroying or disempowering the labor movement (Great Britain, U.S.), which led to a long-term stagnation of wage levels in the U.S., neoliberalism reacted to the crisis by removing the “safety nets” from capitalism, with a flight forward in which the markets – especially the financial sector – were deregulated. In order to avoid collapsing due to its internal contradictions, capitalism effectively left the ground of labor exploitation during the neoliberal turn of the 1980s in order to take to the lofty heights of an economic structure dominated by financial markets. The system reacted to the failure of a change to the industrial structure by establishing the financial system as the “lead sector.”

Capital valorization was thus increasingly simulated on the financial markets under neoliberalism. Since no real capital valorization can be carried out within the financial sphere in the long term, growth in the four neoliberal decades was ultimately fueled by a historically unique boom in the most important commodity that the financial sector has to offer: credit. The capitalist world system thus runs on credit, on the anticipation of future utilization, which is pushed further and further into the future through lending. Credit generates the demand that sustains capitalist commodity production, which is choking on its productivity. This can be seen in concrete terms in global debt, which has risen much faster than global economic output in the neoliberal era: from around 120% in the 1970s to 238% in 2022.[1]

The central mechanism that transformed the increasing financial market-generated debt into real economic growth was the speculative bubble. Since the 1980s, the system has thus been increasingly based on the “hot” air of various speculative bubbles that are constantly forming anew: from the dot-com bubble at the turn of the millennium, when the emergence of the Internet led to wild speculation in high-tech stocks that crashed in 2000, to the real estate bubble in Europe and the U.S., to the large liquidity bubble maintained by central banks, which was only brought to an end by inflation in 2020. When a bubble would burst, there would be a threat of a more widespread crash, which would then be prevented by the emergence of a new speculative bonanza. One could speak here of a veritable transfer of bubbles, in which all the fiscal and monetary policy measures used to combat the consequences of a burst speculative dynamic contribute to laying the foundations for the formation of a new bubble. Ultimately, capitalist financial policy can only put out the speculative fire with gasoline.

The End of Neoliberalism

However, this was not a linear process, but a dynamic one. The costs of stabilizing the global financial system increased more and more as each bubble burst until, in the inflationary phase of monetary policy, outside of the U.S. with its world reserve currency, there was no alternative but to stop the expansionary monetary policy that had been at the root of the boom in the financial markets. Capitalist crisis policy has ridden its financial market-driven, neoliberal horse to death after using this horse to flee from the inner barrier of capital for over four decades. The neoliberal postponement seems to be coming to an end, and the stagflation that has been forgotten for decades is returning on a much higher level. The most important difference between today's wave of inflation and the historical phase of stagflation is that a phase of high interest rates, such as that initiated by Fed Chairman Volcker from 1979, no longer offers a way out in view of the unstable financial sphere.With the end of the global deficit economy, the global deficit cycles, which in fact formed the base of neoliberal globalization, were also damaged. Not all economies became equally indebted in the neoliberal era; export-oriented locations were able to export their production surpluses to deficit countries as part of these cycles. The largest, namely the Pacific deficit cycle between the U.S. and China, was characterized by the fact that the People's Republic, which was rising to become the workshop of the world, exported gigantic quantities of goods across the Pacific to the de-industrializing U.S., thus creating enormous trade surpluses, while a financial market flow of U.S. debt securities flowed in the opposite direction, so that for a time China became Washington's largest foreign creditor. A similar, smaller deficit cycle developed between Germany and the southern periphery of the eurozone in the period from the introduction of the euro to the euro crisis. Globalization was thus not only characterized by the establishment of global supply chains, it also consisted of a corresponding globalization of debt dynamics in the form of deficit cycles, which, as mentioned, grew faster than global economic output – and consequently acted as an important economic engine by generating credit-financed demand. The globalization that brought about these gigantic global imbalances was a systemic reaction, a flight forward from the increasing internal contradictions of the capitalist mode of production, which is choking on its own productivity.

The Return of Protectionism

The euro crisis is, to some extent, a good case study for what is now unfolding globally: As long as the mountains of debt are growing and the financial market bubbles are on the rise, all of the countries involved seem to benefit from this credit-based growth. However, as soon as the bubbles burst, the battle over who should bear the costs of the crisis begins. In Europe, as we know, Berlin has used the crisis to pass on the costs of the crisis to southern Europe in the form of Schäuble's infamous austerity dictates. Now, on a global level, the collapse of the much larger debt-financed deficit economy, which has recently been kept alive primarily by the expansive monetary policy of the central banks, is imminent. Rising nationalism and neo-fascism, the acute threat of world war: they are an expression of this very crisis process. An analogy can therefore be drawn with the pre-fascism of the 1930s, when the fallout from the global economic crisis that broke out in 1929 was exacerbated by a rapid rise in protectionism.Which brings us to Germany's misery. With the erosion of globalization, the long-term economic strategy of strict export orientation pursued since the introduction of the euro by the Federal Republic, whose economic “business model” was based on achieving the highest possible trade surpluses within the framework of the aforementioned deficit cycles, is also failing. With this so-called beggar-thy-neighbor policy, debt, deindustrialization and unemployment are exported to the target countries of the export surpluses. After Berlin had ruined the European crisis states through draconian austerity policies, this export strategy was directed at non-European countries – such as the U.S.[2]

However, this export-focused strategy is increasingly coming into conflict with the protectionist tendencies in Washington, where the Biden administration is effectively continuing Trump's economic nationalism aimed at reindustrialization. Washington is no longer prepared – precisely because of increasing domestic political instability – to continue accepting the high trade deficits that stabilized the hyper-productive world system during neoliberal globalization. These deficits were, of course, only made possible by the dollar serving as the world's reserve currency. As early as mid-2023, the Financial Times described this change in Washington's economic policy strategy, which was initiated by the Trump administration and further promoted by Biden. At its core, it is a protectionist rejection of globalization. By means of a “foreign policy for the middle class,” the White House wanted to counteract the “hollowing out of the industrial base,” the emergence of “geopolitical rivals” and the increasing “inequality” that threatens democracy.[3]

A visible expression of the full onset of deglobalization is nearshoring, in which the U.S. is seeking to replace its economic dependence on the Chinese export industry by building up industrial capacities in Mexico. In addition, German automotive suppliers continue to face the threat of exclusion from U.S. production chains due to provisions of the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act. A substantial concession from Washington is also unlikely, as protectionism appears to be working. German companies in particular are increasingly investing in the U.S. in order to benefit from Washington's subsidies. In effect, there is an economic decoupling between the U.S. and the EU, with Washington pulling away economically while the Europeans in particular have to bear the consequences of the crisis.

The Danger of “Authoritarian Revolt”

Berlin thus spent the 21st century orienting the Federal Republic – and from 2010, in the wake of the euro crisis, the eurozone – towards an export-fixated economic model aimed at achieving trade surpluses in the globalized world economy of the neoliberal era. With the onset of deglobalization, the former export surplus world champion has found itself in an economic policy impasse, which in the medium term not only calls into question the political stability of the Federal Republic of Germany, but also the continued political existence of the eurozone. And it is precisely this return of protectionism that is giving the New Right an additional boost. The properly functioning export economy acted as a kind of civilizational safety mechanism in Germany, with its terrible authoritarian-fascist tradition, as it provided a solid economic argument against nationalism. After all, Germany was a “winner” during the process of globalization.However, it is the German export industry that is currently experiencing a downturn, which is actually just the beginning of the end of the export-focused German economic model. The sharp decline in exports in 2023 has contributed significantly to the poor economic development in Germany, with little improvement expected in the coming years. This also means, however, that the prosperous years made possible by export surpluses will inevitably come to an end for the Federal Republic. The power-political weight of the German export industry will therefore diminish at a time when, for the first time in a long time, Germany will also enter a long-lasting crisis phase, from which the New Right once again threatens to benefit.

Yet it was precisely the functionaries of the large-scale export industry who repeatedly took a stand against the New Right. The AfD and the dull Nazis were seen as an image problem that was damaging the “Made in Germany” brand in its quest for global success. The BDI (Federation of German Industries) and top managers such as Siemens CEO Joe Kaeser were able to cite real economic interests in their arguments against the right. The capital faction that is most resolutely opposed to AfD participation in government is therefore the German large-scale export industry, which is currently losing influence due to the crisis. The reactionary avant-garde within the functional elite, which made pacts with the AfD and the Querfront very early on, consists of small business owners and SMEs, as can be seen from the links between the association of “family entrepreneurs” and the AfD. Capitalists focused on the domestic market (“Müller Milch”) also appear to be more inclined to consider far-right options.

The AfD is already the second strongest force at federal level. The fact that the rise of the AfD took place during a phase of relative economic prosperity shows just how thin the civilizational ice has become in Germany; it was fueled by German fear of crisis, not by an actual outbreak of crisis, such as the one southern Europe had to endure during the euro crisis. Since the refugee crisis, the entire bourgeois-liberal anti-fascism, which was largely in line with the arguments of the export industry, has emphasized the economic “usefulness” of globalization, open borders for the movement of goods and immigration: refugees are economically useful due to the ageing of the Federal Republic, the export country must remain attractive for skilled workers, at least according to the common arguments. However, these narratives cultivated in the liberal mainstream will disappear as soon as stagnation and recession become entrenched in Germany, while exports will continue to decline in order to give further impetus to the “German fear” that so readily turns into hatred of the socially disadvantaged.

The crux of the matter is that this authoritarian revolt will never come to power unless a substantial part of the ruling elite opts for this fascist option. And there are signs of an open split within the German ruling elite regarding the participation in government of a party that is drifting towards the extreme right. This is the decisive breach in the dam: will entire factions follow the previous AfD sympathizers such as Mr Müller von der Müllermilch or the Mövenpick billionaire Baron August von Finck? In the middle class? Among family entrepreneurs?

Fascist movements only come to power in times of crisis when the shocks and upheavals have reached such an extent that functional elites perceive these movements as the “lesser evil.” To put it vividly: only when capital managers are so deeply mired in the crisis that they are up to their necks in water do they hold their noses and reach out to the extreme right. And then there is no stopping them, as the fascist authoritarian revolt, which always craves the approval of the authorities, is further fanned by this (which, incidentally, also defeats the left-wing intention of shaking up their supporters by unmasking the powerful fascist backers. Authoritarian characters are not deterred but attracted by the cronyism of AfD functionaries and billionaires).